Father-Son theology (FST) is built on the foundational truth that we should see God as Father and ourselves as His children.

The best place to commence our study is not in Genesis 1:1 with the words, “In the beginning, God.” We should go back earlier than that. A better place to start is with God and His heart before the foundation of the world. Under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, Paul, the apostle, revealed to us God’s heart, intentions, and plans:

He chose us in Him before the foundation of the world, that we would be holy and blameless before Him. In love He predestined us to adoption as sons and daughters through Jesus Christ.Eph. 1:4-5

In love, God foreordained that He would have children. God decided His sons and daughters will be holy and blameless. He foreordained that this would be accomplished through Jesus Christ.

There you have the core message of Father-Son Theology.

You should already relate to this message because God created and fathered you. There is a longing in your heart to know God as Father and yourself as a child of Father-God. Your heart longs to know whence you came, who you are, and who you will become.

These are subjects addressed in theology.

For many Christians, such as myself, theology has always been the most exciting and rewarding study. However, one of the problems with learning theology is the communication gap between professional theologians and the average Christian who is hungry to understand God. Fortunately, theology does not have to be difficult to understand. Albert Einstein is often attributed with saying, “You do not understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother.”1 I have met some pretty sharp grandmothers, but this book has been written in simple language so all grandmothers can understand.

It also delves deep and progresses quickly classenough to captivate the attention of those already studied in the field. It is written as a textbook that may be used for personal study or in a theology classroom. It defines theological terms in bold letters. Those emboldened terms are defined in the context. This book introduces readers to the historic Church’s major doctrines, along with biblical truths at the forefront of current Christian thought.

This work is subtitled Biblical Theology Presented in a Systematic Way. This terminology accurately describes what is communicated throughout Father-Son Theology but calls for an explanation.

Typically, biblical theology and systematic theology are separated from one another.2 Biblical theology traces the development of truths about God as they are progressively revealed in the Bible. Systematic theology3 takes one major subject at a time and summarizes what the whole Bible teaches on that subject. Systematic theology also takes biblical truths and makes them reasonable within current human understanding, which requires taking into account philosophy, traditions, and culture.

Biblical Truths about God → Biblical Theology

Biblical Truths about God + Philosophy, Traditions, & Culture → Systematic Theology

This means a systematic theology that is developed for Christians who live in the Western world has been adapted to Western philosophy, Western traditions, and Western culture. A systematic theology developed for Western people differs from a systematic theology developed for a different culture, such as the Oriental or African culture.

Bible colleges and seminaries, under the authority and influence of Western Christianity, almost always teach theology from a Western perspective. Thoughts are organized into major categories that are comfortable to the Western mind, categories such as the nature of God, the nature of humanity, sin, salvation, and so on. Those Bible colleges and seminaries all share fundamental thought patterns that conform to the Western mind.

FST attempts to present biblical thought in a manner that is understandable to people from all cultures around the world. FST still organizes biblical thought into the traditionally used categories. This allows biblical truths to be “presented in a systematic way.” Although FST uses the major Western categories, discussions within those categories are built on biblical thought separated from Western philosophy, traditions, and culture. For this reason, FST should be considered a biblical theology.

To understand why it is essential to separate theology from Western philosophy, traditions, and culture, it will be necessary to talk about critical steps in the development of Western Christianity. It will also be necessary to explain how and where Western theology went awry.

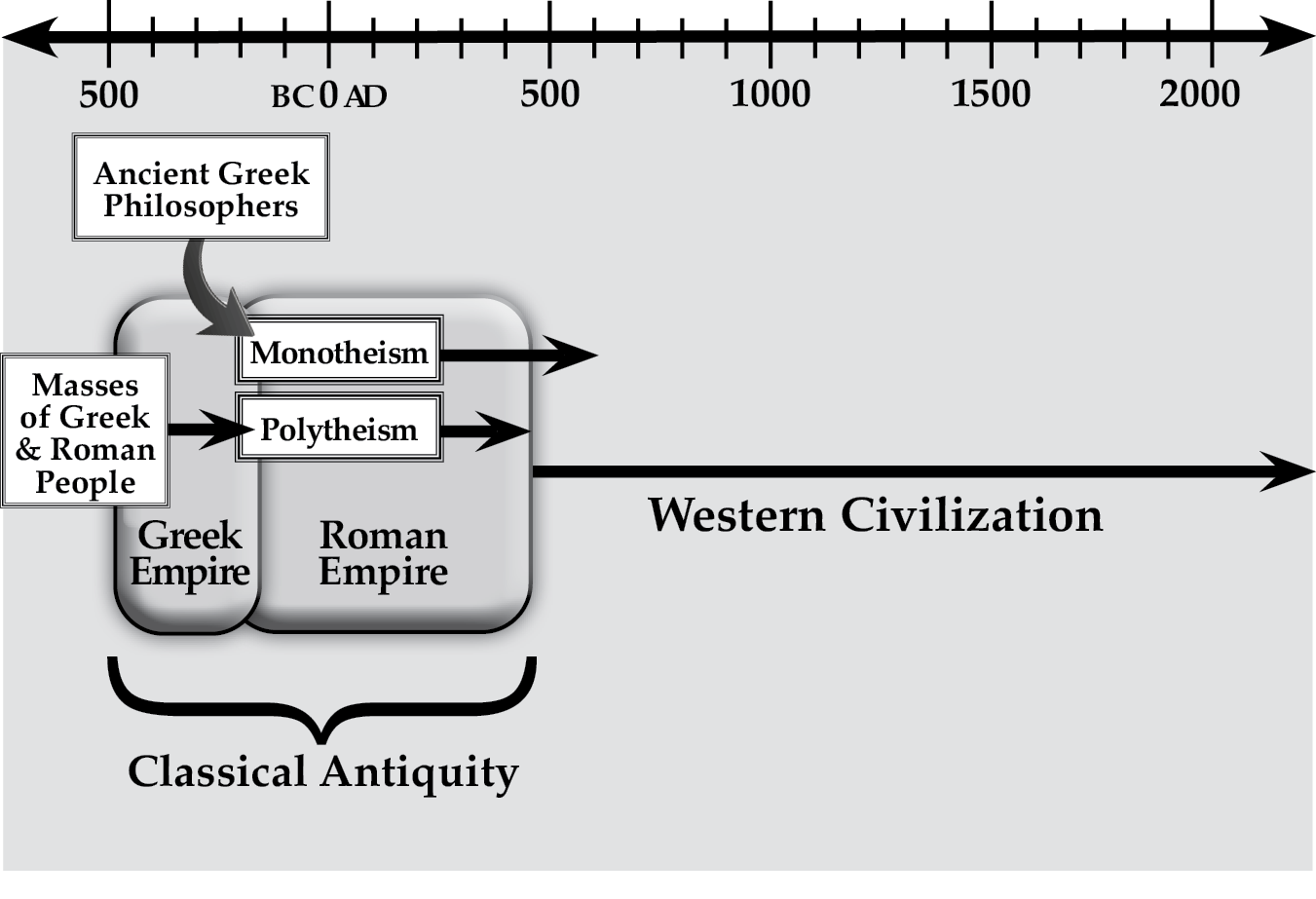

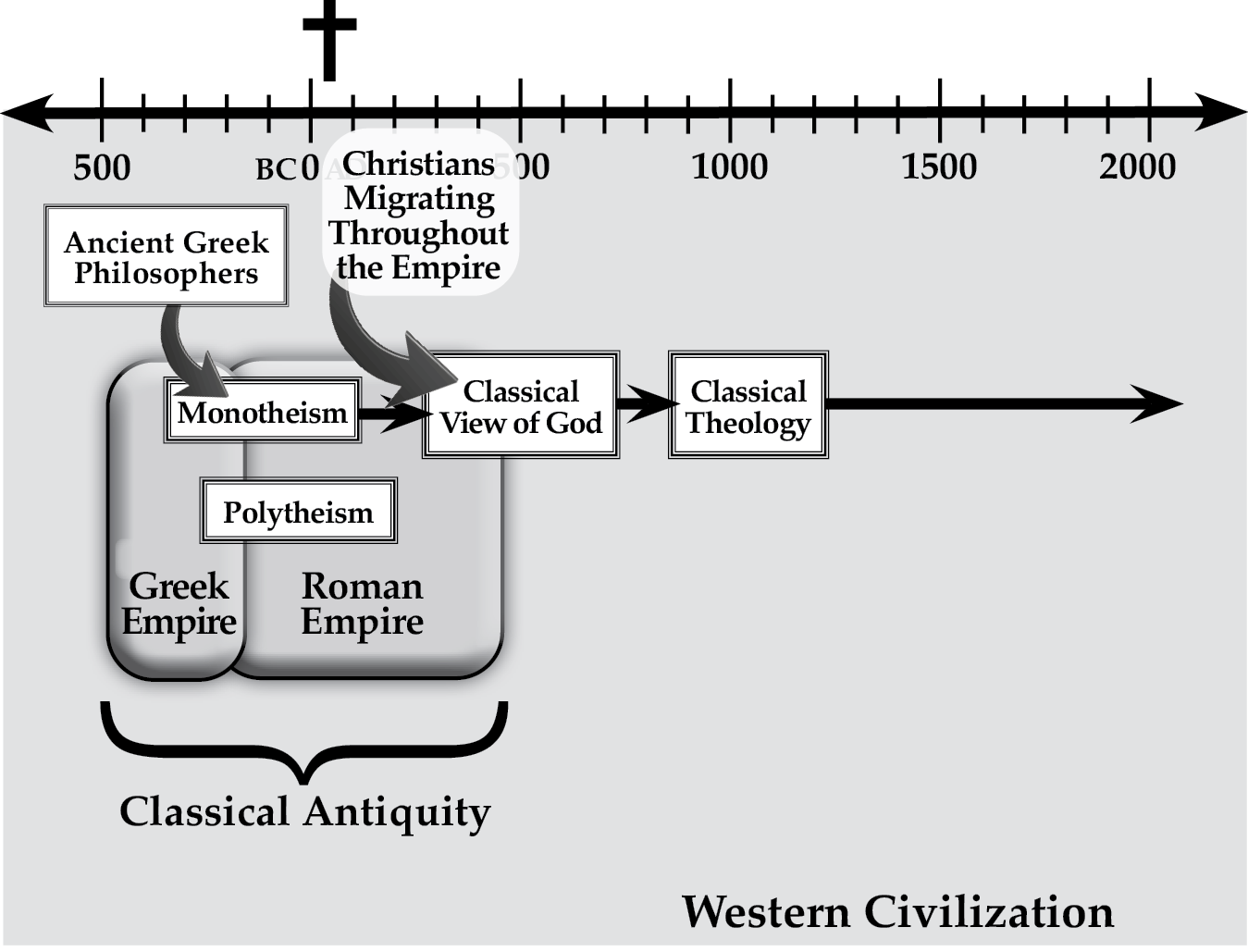

Every reader will benefit by having a simplified picture in their mind of the historical development of Western civilization. To start building that picture, the next eight paragraphs will provide the necessary overview of the development of Christianity within Western civilization.

When historians discuss the foundation of Western civilization, they typically point to when the ancient Greek and Roman Empires ruled the area around the Mediterranean Sea. Influences upon Western civilization existed long before this time, but later,4 we will explain why historians point to the Greek and Roman Empires as the primary formation period of Western civilization. That period extended from the 8th century BC to the 6th century AD and is called Classical antiquity.

Classical antiquity provided a unique intellectual environment profoundly influenced by the ancient Greek philosophers: Plato, Aristotle, and Plotinus.5 For our study, it is important to know that the masses of Greek and Roman people were polytheists (believers in many gods). The ancient Greek philosophers were introducing thoughts that led to monotheism (a belief in one god).

During the 1st century, Christianity emerged from the Jewish world and spread throughout the Roman Empire. By then, the Greek and Roman intellectuals had been discussing the one god of the ancient philosophers for at least three hundred years. So when the early Church fathers wrestled with the issues of their day, discussions about God were guided down a path that corresponded to the discussions about the one god of that period. Some of the Church fathers proclaimed that the one god of the philosophers was the God of the Bible.6

Throughout Volume I, we will see how some Greek and Roman thought syncretized with Christian truths about the nature of God. That resulted in what is today called the Classical view of God.

Modern Christians are referring to the Classical view of God when they ascribe to God the attributes of timelessness, perfection, immutability (unable to change), omnipotent (all-powerful), omniscient (all-knowing), and omnipresent (present everywhere). These and other attributes assigned to the Classical view of God will be explained in the body of this work.

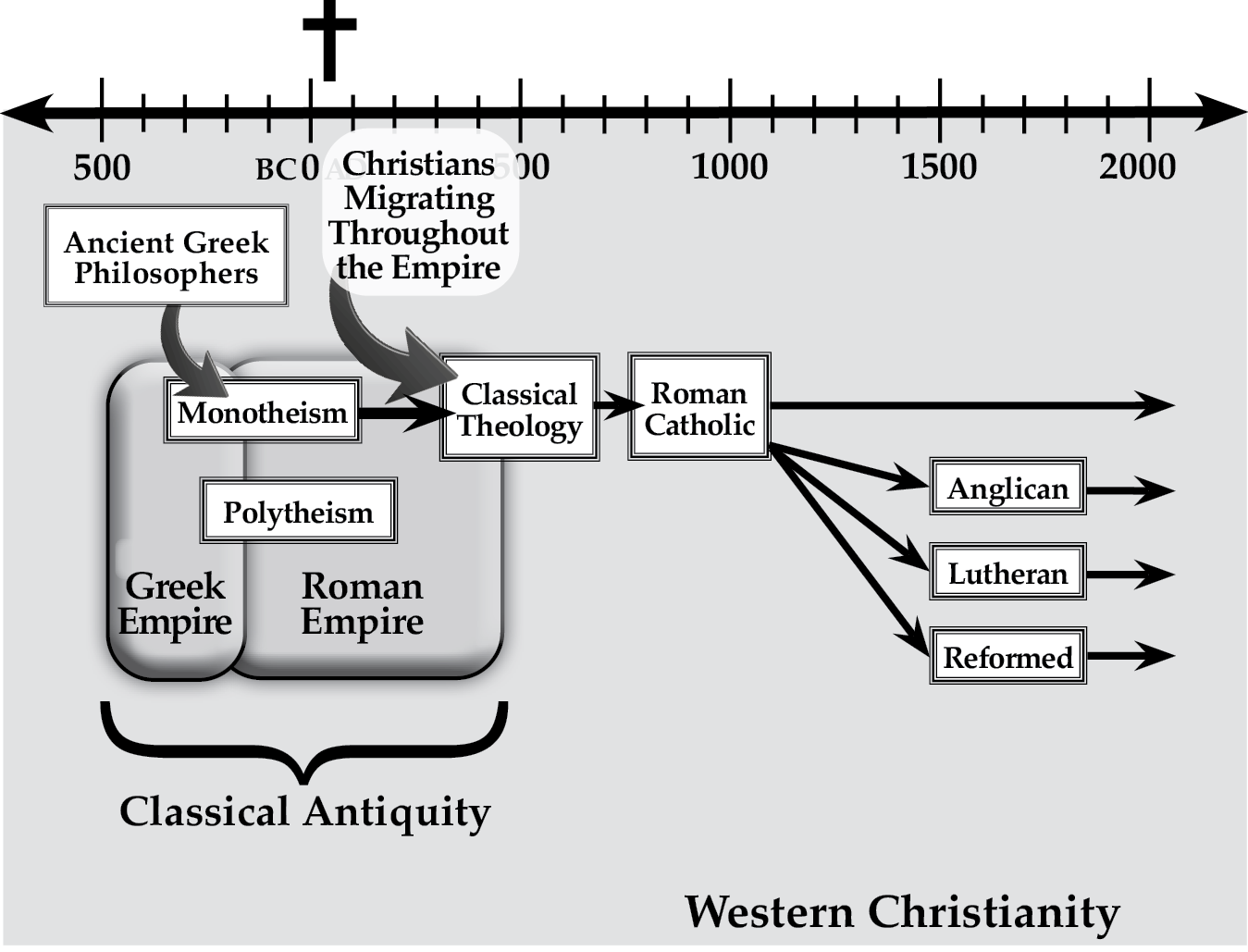

The theological system that developed out of the Classical view of God is called Classical theology (CT).

Classical View of God → Classical Theology

Classical Theology is the foundation for Western Christianity. This includes Roman Catholicism and Protestant Christianity. Although Protestantism includes thousands of groups today, here we refer to the three primary Protestant streams that split from Roman Catholicism in the 16th century: the Anglican,7 Lutheran, and Reformed traditions. These were all built on the Classical view of God.

For almost 2,000 years, the Classical view of God and CT have been the well-established standards throughout Western Christianity. Although modern Bible colleges and seminaries each teach their distinctives about the Christian faith, most Christian institutions in the Western world build their theology on the Classical view of God.

Throughout this book, we will be talking much about CT and comparing it with FST. Therefore, it will be helpful now to clearly identify what is meant by CT.

Thomas C. Oden, who is considered one of the most influential theologians of the 20th century, presents a well-accepted explanation in his book, Classic Christianity. He associated CT with the fundamental thoughts of Christianity that were agreed upon by the Doctors of the early Church.8

The title “Doctor” has been given to leaders who made significant contributions to theology. The Doctors of the early Church in the West were Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory the Great.9 The Doctors of the early Church in the East were Athanasius, Basil, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Chrysostom.

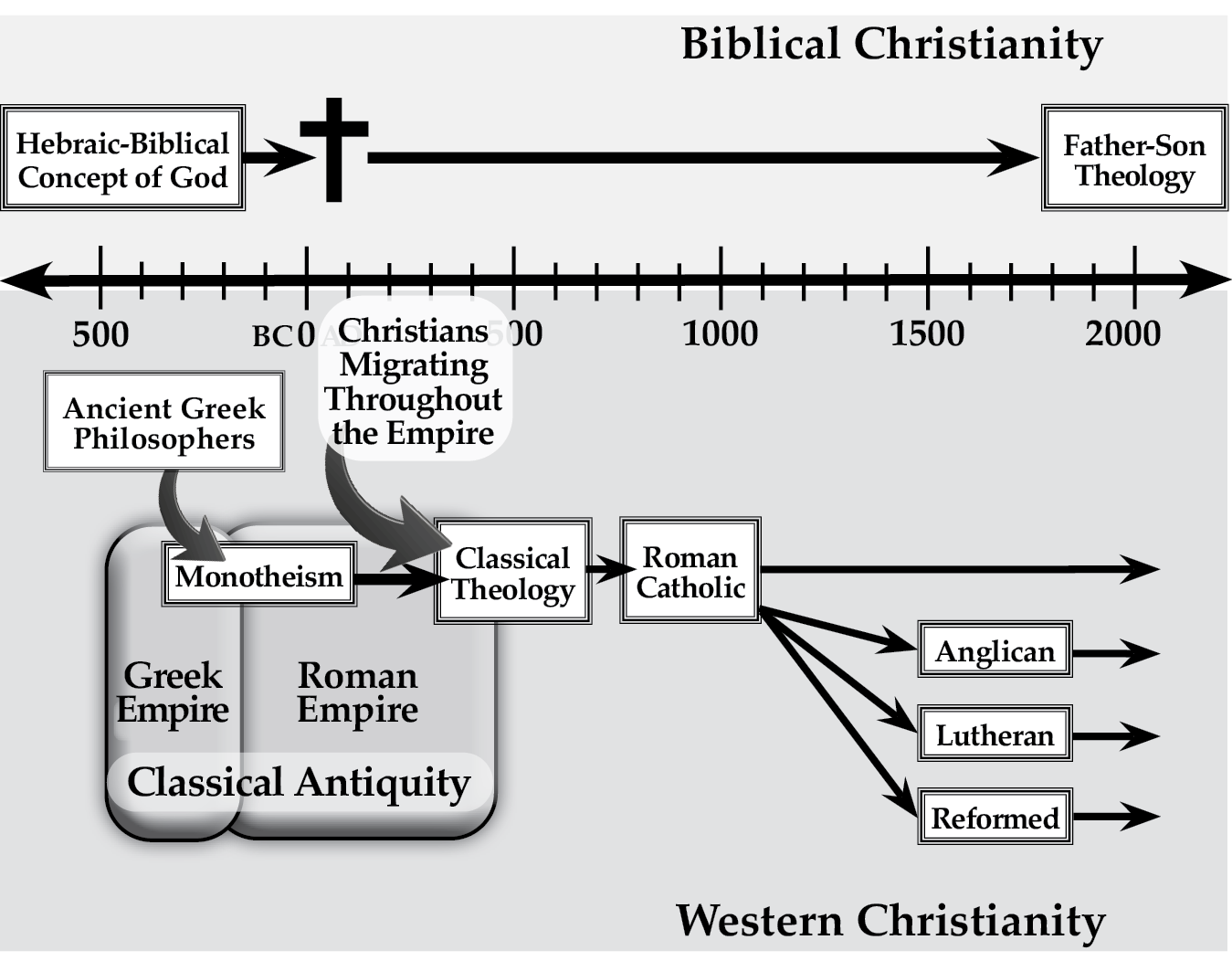

Throughout this book, we will be contrasting the Classical view of God with a more biblical view of God. To develop the biblical view, we will examine the revelation of God in the Bible within its historical Hebrew and Jewish setting.10

Contrasting the Classical view of God with a Hebraic-biblical view of God may be offensive to Christians holding to the Classical view of God. After all, they believe their view of God is the biblical view of God. I do not mean to offend anyone. I am not trying to uproot all points of CT. I simply want to identify and then correct some flaws in its foundation. To accomplish this, I must point out and contrast the differences between the Classical and Hebraic-biblical views of God.

Exposing incorrect ideas that modern Western Christians have about God requires radical surgery because the foundation of Western civilization was laid down centuries ago by the ancient Greek philosophers. With Greek thought deeply embedded in Western civilization, extracting the thoughts related to God may be painful, but when the healing process completes, you will see the truth of FST over and against CT.

Notice that I am associating the Hebraic-biblical view of God with FST. You will see that the Hebraic-biblical view of God leads to FST.

Hebraic-biblical View of God → Father-Son Theology

I coined the terminology Father-Son theology, but I am not overly attached to the name. Other leaders, cleverer than me, may rework my thoughts and come up with their versions of FST. I pray this will happen. They may originate and appropriate more revealing terminology. That would be okay because I hope leaders will wrestle with these ideas enough to make them their own. For now, I need a label to refer to and summarize the biblical theology presented throughout this book.

As we develop FST, the associated ideas will be compared with CT. The differences will be discussed but also shown in diagrams. When helpful, a timeline will be offered. The development of Western Christianity, which is built on CT, will be shown below the timeline, while biblical Christianity, which leads to FST, will be shown above the timeline.

As we develop FST, you will see that this perspective recognizes some free will in the nature of humanity,11 but FST is not a variation of Arminianism.

Christians trained in Reformed theology (RT), which emphasizes God’s total sovereignty, tend to label any theological view that questions God’s divine predestination of all things as Arminian, the theological view that emphasizes humanity’s free will. Hence, adherents of FST may be accused of being Arminian, but that is far from the truth.

Arminian theology developed in the late 16th century as certain leaders began pointing out ideas within RT that they saw as inconsistent with the Bible. Still, RT and Arminian theology have more in common with each other than either have with FST. This is true because both RT and Arminian theology were built on the Classical view of God. Both were also developed within the Western culture.

FST attempts to reach back before Christianity was syncretized with Greek and Roman thought. It attempts to build on the Hebraic-biblical revelation of God, rather than the Classical view of God. FST also attempts to separate itself from Western culture. Of course, no one can fully escape their own culture, but FST moves us in that direction.

In the first and second editions of this book, I pointed out some errors made by theologians who have promoted CT and RT. However, I avoided as much as possible naming individual theologians. Readers of those first and second editions commented that I should not refer to their errors without giving names and references. For this reason, here in the third edition, I have added more direct quotations and provided the corresponding references.

However, I still want to minimize criticism of the beloved Christian brothers and sisters who are committed to those views. Anyone who associates with Christians committed to CT or RT knows that there are devoted followers of Jesus in each stream of Christianity. Each of these streams has given birth to Christ-like character and brought tremendous blessings into all areas of society.

I owe a great debt to each of these Christian traditions, having been raised as a child in Classical Christendom, then later, discipled and firmly planted in Reformed thought as a young adult.

Because Father-Son Theology is a long, extensive work, some readers may be tempted to jump ahead to different portions. Jumping around may lead to misunderstandings because the thoughts are developed progressively throughout these volumes. If you are prone to jump ahead, please read Volume I, Sections A & B, so you can first identify the fundamental errors of Western theology that are being corrected throughout Father-Son Theology.

Some readers may react negatively to the title, Father-Son Theology. Using male terminology (Father-Son) may cause concern for those who long for a gender-neutral theology.

A gender bias can indeed result from referring to God as Father, but the term Father is not culturally conditioned. It is a proper name for God given by divine revelation, e.g., Mt. 6:9, Eph. 1:3, Rom. 8:15, and Is. 64:8. It is fundamental to our understanding of the Trinity, and Jesus instructed His followers to call God “Father.”

Concerning the term “son,” there is an unfortunate gender bias implied, but the gender-neutral alternative is “child,” which brings to mind an immature individual. That would create a misleading image because a significant point of FST is Father-God’s desire to raise mature individuals.

Of course, we could use “son and daughter” or the opposite order, but the title, Father-Son-and-Daughter Theology, introduces a confusing string of words. Rather than complicating the name of this theological perspective, please understand “son” as referring to any of God’s maturing children, male or female.

As you get into this work, you may think I am too passionate about ridding Western Christianity of the influence of the ancient Greek philosophers, especially Plato, Aristotle, and Plotinus. You may be correct in that criticism. I am determined to incinerate the residue of those philosophers and then blow away the dust!

1: Some scholars doubt that Einstein said this and suggest it is a variation on a statement made by Ernest Rutherford.↩︎

2: Many scholars trace the separation between biblical and systematic theology to 1787, when Johann P. Gabler delivered an inaugural address at the University of Altdorf on the distinction between biblical and dogmatic theology.↩︎

3: The label “systematic theology” is sometimes used interchangeably with “dogmatic theology,” but the latter refers to a systematic theology that has been authoritatively affirmed by an organized church body, such as the Roman Catholic Church, Anglican Church, Lutheran Church, etc.↩︎

4: Discussed in the Introduction to Section I in Volume I.↩︎

5: It is possible that Plotinus was not Greek, even though he is considered a philosopher of late antiquity and he built on the foundation of Plato.↩︎

6: This is further discussed in I:I:81.↩︎

7: Although the Anglican Church separated from Roman Catholicism in the 16th century, officials of the Anglican Church generally see their origin when Augustine of Canterbury came from Rome to the British Isles toward the end of the 6th century.↩︎

8: Thomas C. Oden, Classic Christianity (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1992), xvi.↩︎

9: Roman Catholicism recognizes several more leaders as Doctors of the early Church.↩︎

10: “Hebrews” refers to the descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who were the ancestors of the Jews. Those living in the Promised Land after the return from exile in the 6th century became known as the Jews.↩︎

11: Free will is discussed in several places, most thoroughly in Volume IV, Section F.↩︎